I am really excited to start communicating about my new theory of natural reward. The purpose of this blog will be to give background information to my published works and to stimulate discussion. I encourage comments and criticisms.

In this first blog post, I will give a simple explanation of what the theory of natural reward means on the backdrop of previous advances of science.

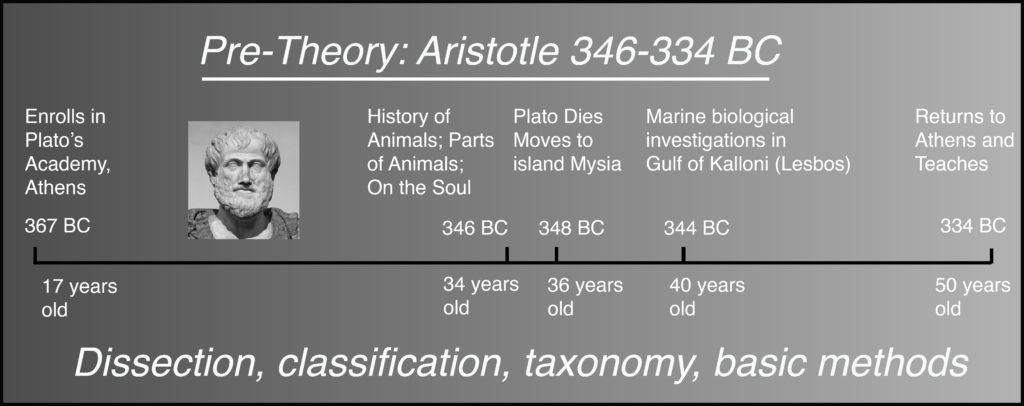

About 2300 years ago, Aristotle carried out the first detailed biological investigations on record. His approach was observational. He dissected various animals, and asked many interesting questions about physiology. Aristotle argued that nature “does nothing in vain,” and that complex organismal traits originate for their ultimate apparent function. Aristotle’s teacher was Plato, and one of his students was Alexander the Great.

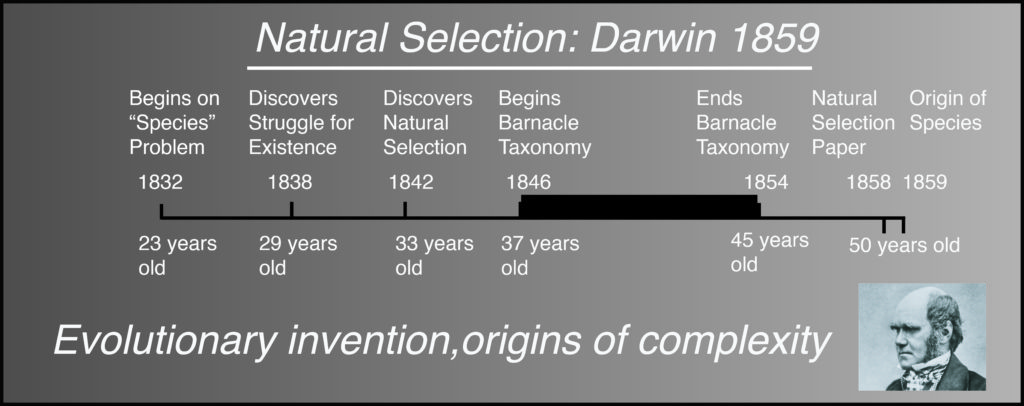

About 160 years ago, Darwin made the first great advance in biology since Aristotle. Darwin also carried out many taxonomic and observational investigations. Darwin came up with a theory that explains the historical origin of complex traits. Instead of appealing to final causes, Darwin reasoned that complex traits are built gradually by a short-sighted force he called natural selection. The key to Darwin’s theory was the assumption of resource limitation, which leads to a struggle for existence, natural selection and the survival of the fittest (best adapted).

Following Darwin’s death, there was a long-term deterioration in the understanding of evolutionary theory. This started when Fisher redefined fitness from Darwinian adaptedness to net reproductive success, and argued that natural selection will increase an aspect of fitness so defined. Many authors assumed that natural selection thus acts to maximize fitness, and that one could explain the origin or success of complex traits by appeal to the final cause of fitness maximization (e.g., Dobzhansky and Hamilton) or gene selection (Williams and Dawkins). The rise of teleological theories resulted in an eclipse of Darwinism. There was progress in empirical work and applied models, but general theory remained haunted by teleological doctrines.

Research I carried out on social amoeba caused me to question what I’d learned in my textbooks (in a later post I’ll explain how). This research led me to ask, “what argument did Darwin use to define the levels of selection and time frames of evolution?” I found that Darwin used his notion of “the struggle for existence,” which is itself based on an assumption of resource limitation. Most previous authors had misinterpreted Darwin’s writing because of their prejudices derived from learning evolutionary theory from second-hand works (textbooks, etc.).

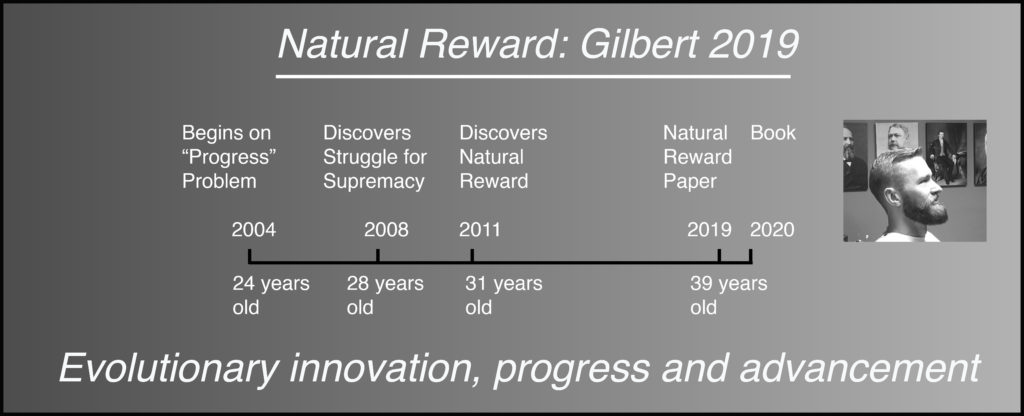

As I explain on the page devoted to the theory of Natural Reward, I developed a theory that invokes resource abundance, a struggle for supremacy, natural reward, and the success of the innovative. As the timeline above shows, the sequence of my discoveries is similar to Darwin’s. Even the number of years between key discoveries is similar. The main difference is that I did not spend eight years studying barnacles, though I could have easily spent that trying to become a tenured professor (if I had “lucked out” and gotten an assistant professorship).

One thing novel that comes from this timeline comparison is that the discovery of a particular struggle and the force associated with it are independent discoveries. Indeed, I realized the difference because it was three years between when I discovered the importance of the struggle for supremacy and when I recognized natural reward as an alternative force associated with it. This also made me realize that Darwin uniquely discovered natural selection. Wallace discovered the importance of the struggle for existence but he did not discover natural selection.

Some will say I am arrogant because I just compared myself to Darwin. But my purpose is only to point out the similarity of sequence of discoveries and raise the question of whether I am correct. Also, some of my friends think that I have been extraordinarily slow in coming out with my theory. But this comparison confirms that I have been no slower than Darwin in first publishing my theory.