Evolutionists often claim that evolution is a fact. But whether evolution is a fact depends on the meaning of evolution. With reference to Darwin (1859), evolution could mean: (1) descent with modification, (2) natural selection plus chance as an explanation for apparent design, (3) a Law-Making Creator, and (4) long-term progress toward superior forms of life. Making these distinctions is important because, for example, (2) might not be as well supported as most evolutionists believe, while (3) is undergoing a revival.

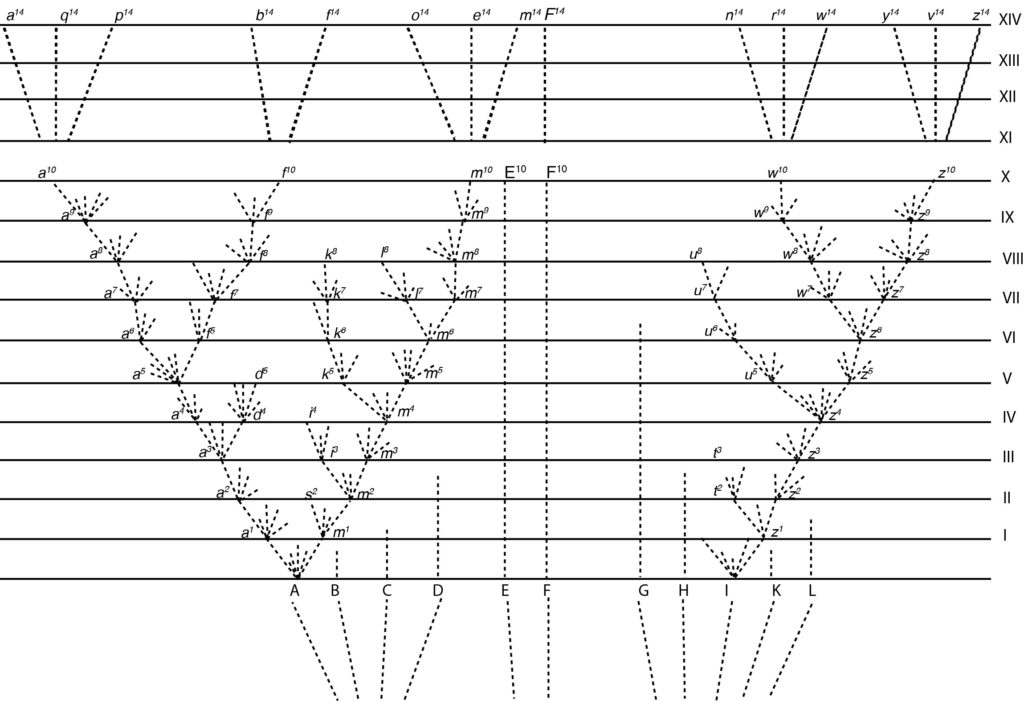

The first possible meaning of evolution is descent with modification. This is illustrated by the “tree of life” (Fig. 1). Under the tree of life, the reason that some groups of species closely resemble each other (e.g., frogs more closely resemble other frogs) is because they share a recent common ancestor, as might be represented on a stem before a branch. This now makes intuitive sense to us today. Most people accept this meaning of evolution applied to most organisms, though some for religious reasons don’t think it applies to primates. The case for evolution thus defined is now so well established by genetic and phylogenetic studies even as applied to primates, however, that it might as well be considered a fact.

Fig. 1. Evolution as fact. Descent with modification illustrated by Darwin’s first tree diagram. In celebration of this well-supported theory is a large collection of tattoos (e.g., Google “Darwin tree tattoo” or “Hillis diagram tattoo”).

The second possible meaning of evolution is natural selection plus chance explains apparent design. Before 1859, it was widely thought that complex traits of organisms, which appeared designed for some purpose, were built teleologically for that purpose. The idea that final causes explain complex design went all the way back to Aristotle. However, Aristotle did not provide a “mechanism” to explain how complex design came about, and many later took Supernatural Intelligence to be the mechanism. Under the theory of Independent Creation, popular in Darwin’s time, God created species independently of each other in their particular places in nature. Species did not come from other species, nor did they change with time; they originated suddenly in Divine acts of Creation. There were various anomalies to this view of life, which had caused some philosophers to doubt the argument from design, and suggest that it was the design of natural laws that should be taken as evidence for God. However, the vast majority of biologists endorsed the argument from organismal design, sometimes with modifications.

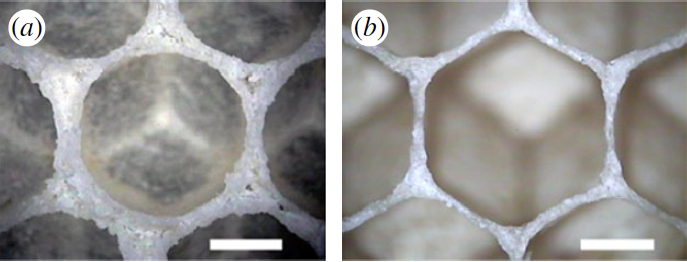

The solution Darwin gave to replacing the paradigm of Independent Creation was to provide a plausible explanation for apparent design in nature, and then compare the theories of descent and Creation. Darwin’s explanation for apparent design was to break a complex trait into simpler components, infer historical sequences through which sub-traits evolved based on comparative data, and apply the optimization logic of natural selection only to the sub-traits. Darwin himself applied this method for deconstructing complexity to several traits, including the vertebrate eye and honeybee honeycomb (Fig. 2). The consequence of Darwin’s “plausibility” argument was that it meant the instances of apparent design in nature were not necessarily evidence for Independent Creation. Thus, the theories of Creation and descent could be compared head-to-head.

Fig. 2. Evolution as theory. Darwin proposed his theory to explain apparent design in nature by use of examples. In the honeycomb example, Darwin argued that bees’ simpler instincts for forming spherical burrows and saving wax led to a complex structure. In the picture here, (a) bees form cylindrical cells standing a certain distance apart, and then (b) using their wax-saving instincts, they gnaw the cells until they can sense that they are encroaching on a neighboring cell. In contrast, evolutionists today often explain complex traits by appeal to final purpose, like maximizing fitness (Photo credit: Karihaloo et al. 2013).

It is important to stop and examine Darwin’s strategy. Darwin’s attack on Creation was not a direct comparison of his novel theory of apparent design to the Creation theory of apparent design, but a comparison of his theory of descent to the theory of Independent Creation. This was a smart strategy for three reasons. First, it allowed Darwin to compare a theory that made sense of many well-known facts on distribution, development, and embryology, to one that made no sense of those facts. Second, it emphasized a theory of descent that was similar to that already proposed by others (e.g., Lamark and Chambers), except now slightly modified and more coherent. Third, it allowed Darwin to distract attention away from his rash new theory for apparent design, which seemed to have little evidence compared to its radical claims. It must be remembered that at the time, most people believed that complexity came from intelligence, or otherwise from a natural law acting for final causes; and not from a blind and short-sighted force combined with chance. Even today, many people including evolutionists resist the logic Darwin’s theory, instead deferring to teleological explanations that invoked final causes.

If most of the evidence leading to the adoption of Darwin’s theory was evidence for descent, this raises the question of how much evidence has accumulated for Darwin’s theory of apparent design. In fact, the evidence is not nearly as well accumulated as most evolutionists think. The main reason for this is that most evolutionists assume that Darwin’s theory for apparent design was just natural selection plus random variation. This ignores the role of chance in the sequence of successive modifications of adaptive traits, as well as how subtraits can incidentally synergize (Fig. 2). It also leads to the assumption that natural selection optimizes whole complex traits, or even whole organisms, to final goals. Consequently, there is still almost no verbal theory explaining Darwin’s method in succinct and general terms, little computational theory for the origin of complex traits that formalizes Darwin’s method, and few experimental evolution experiments and computer simulation studies demonstrating how complex characters are built. There is also no formal mathematical theory of Darwin’s method, though this would probably be inappropriate (computation being more appropriate). Thus, Darwin’s theory of apparent design, though still showing promise, remains somewhat speculative and far from qualifying as “fact.”

The third possible meaning of evolution is Darwin’s suggestion of a Law-Making Creator. Darwin proposed that it made more sense that God created several simple laws (variability, reproduction, selection, etc.), from which species originated, than planning every fresh act of Creation independently. If God instead planned every detail of Creation, He would have intentionally planned for wasp species that make a living terrorizing their caterpillar victims without empathy (Fig. 3), or queen bees that kill their fertile daughters. Of course, one does not have to agree with Darwin’s reasoning, which appears pessimistic to some, for invoking a Law-Making Creator. Some people might argue that God created natural laws knowing all that would happen—and that if wasp larvae kill caterpillars, it is Good (e.g., wasps help save man’s crops because caterpillars are pests). Darwin took a different stance probably because he lost his favorite daughter to disease at a young age, and he could not see a Benevolent Creator having planned such an event. But even though some people might also interpret such deaths as Good, whether one believes in a Law-Making Creator is independent of that particular stance. It is possible to examine the hypothesis as either true or false independent of why. This raises the question of whether Darwin’s idea of a Law-Making Creator is scientific.

Fig. 3. Evolution as speculation. Some wasp species have larvae that eat their caterpillar hosts alive from the inside out, preserving the nervous system for last. Shown here are cocoons of parasitoid wasps hatching from a caterpillar. The speculative hypothesis is that God created several simple laws and did not plan for the creation of these parasitic species. Photo Credit: Pavel Kirillov.

I would suggest that Darwin’s idea of a Law-Making Creator, independent of the question of how omniscient God is, or even that a Designer reflects a particular deity, could be considered a speculative scientific hypothesis if there were reasonable alternatives to it. Physicists state several hypothesis to explain why the fundamental parameters of physics, like the masses of particles or the density of dark energy, are such that galaxies and life are possible. The alternative hypotheses to explain why galaxies and life are possible include such ideas as a multiverse and Design, though in the latter case the identity of the Designer is left unspecified (Tegmark et al. 2006). Most physicists prefer hypotheses other than Design, but they still include it. Darwin’s idea of a Law-Making Creator could also be seen as a speculative hypothesis if it had similar alternatives (and in fact, the alternatives could be the same, because galaxies must form for natural selection to operate).

The fourth possible meaning of evolution is Darwin’s idea of long-term progress toward superior forms of life. Darwin’s theory of descent implied that all species had evolved from “one or a few forms,” and thus that there must have been major long-term increases of complexity, diversity, and ability to evolve (or diverge in character). Darwin’s theory required major trends of evolution, much as Newton’s theory required the force of gravity. The question is: could Darwin’s theory explain those trends? In The Origin of Species, Darwin emphasized that natural selection is a blind and short-sighted force, expected to lead to adaptation to context-dependent environments and imperfection. However, Darwin also argued that new species should beat their “inferior” ancestors, and that there could be a struggle among “the larger groups,” leading to success of those that are variable and tend to diverge in character (Fig. 4). However, Darwin never clearly distinguished such a larger struggle from the struggle for existence, nor any different deterministic (non-random) force associated with it.

Thus, it appeared that Darwin was arguing that the struggle for existence and natural selection led to long-term progressive trends. After Darwin received criticisms from his friends that his theory had contradicted itself, he did not respond by delineating an alternative struggle or force. Instead, Darwin replied that if it was necessary to invoke such other force, that he would reject his whole theory as “rubbish.” Soon after writing The Origin, Darwin stopped his research program meant to show how newer species are somehow superior (his “botanical arithmetic”), and abandoned his pursuit of developing a macroevolutionary theory. He moved on to fleshing out his theories of descent and design (his works on variation, orchids, etc.), which remained his focus until he died.

Fig. 4. Evolution as incomplete theory. Darwin argued that there was a struggle between “larger groups,” which would cause species with a tendency to vary and ability to diverge in character to give rise to more new species and conquer those that are not variable. In Darwin’s diagram pictured here, the initially variable species A and I give rise to nearly all of the descendant species. Although this suggested an explanation for long-term progressive trends, it did not delineate an alternative struggle or deterministic force associated with it. It thus contradicted Darwin’s theory based on the struggle for existence and natural selection, which is why Darwin abandoned it (see Darwin 1859 and Gilbert 2019 for more information; redrawn from Darwin 1859).

Although Darwin abandoned a quest for a complete theory that also explains the major trends of evolution, more recent empirical discoveries showing the typical form of competition in macroevolution, as well as a synthesis between fields, has lead to a new theory of macroevolution. This theory identifies an alternative struggle and deterministic evolutionary force (Gilbert 2019). Interestingly, this new theory suggests that Darwin was on the right track in his macroevolutionary pondering (Fig. 4), but that he was held back by his lack of understanding of the form of competition that occurs in macroevolution. Darwin was unaware the macroevolutionary competition is usually an indirect race to innovate, rather than a direct competition between co-existing alternatives. Without realizing the operation of a different type of competition, he failed to distinguish a separate evolutionary struggle, or the force associated with it. It seems that it would have been very difficult or impossible for Darwin to have developed such a theory at the time, because economic theory had not yet been sufficiently developed to provide the necessary analogies and metaphors.

So, is evolution a fact? If by evolution we mean descent with modification, then evolution is a theory that is now as well established as any fact of science. If by evolution we mean natural selection plus chance as an explanation for apparent design, then evolution is an under-developed theory, which is in need of further development. If by evolution we mean Darwin’s idea of A Law-Making Creator, then evolution is a hypothesis that would need some reasonable alternatives before it is scientific. If by evolution we mean Darwin’s idea long-term progress toward superior forms of life, then evolution is an incomplete theory that is now being completed.

Darwin, C. R. 1859. On the origin of species. John Murray, London.

Gilbert, O.M. 2019, Natural reward as the fundamental macroevolutionary force. arXiv:1903.09567

Karihaloo, B.L., Zhang, K. and Wang, J. 2013. Honeybee combs: how the circular cells transform into rounded hexagons. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 10: 20130299.

Tegmark, M., Aguirre, A., Rees, M.J. and Wilczek, F., 2006. Dimensionless constants, cosmology, and other dark matters. Physical Review D 73: 023505.