UT OLLI Talk “On the Advancement of Life” Part 1 of 3

I had the pleasure of speaking for the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI) at UT Austin on April 24, 2020. This program is for people aged 50+ who want to explore new ideas and frontiers of knowledge. Due to Covid, I gave the talk online with Zoom. I based the talk on my paper, Natural Reward Drives the Advancement of Life, which is essentially a proposal for my book, The Advancement of Life.

Below, I will give the transcript of the talk. This includes an introduction section in Part 1 and a Q&A in Part 3. To improve legibility, I removed some unnecessary verbiage.

Moderator (Anita Knight):

I am going to say welcome to everybody we have 44 participants.

Now, at 10:59, I am going to turn it right over to Dr. Gilbert introduce himself but I just wanted to welcome everybody to our third session and we are halfway through the Spring session with OLLI.

We did get an email with a two-page handout from Owen. If you did not get it beforehand, I am sure you will see it later, and he will refer to it.

So welcome to Dr. Gilbert and welcome everybody else…be sure and put your questions in the Q&A bar as you go and we will answer them all at the end.

Dr. Gilbert:

Okay! I guess we are ready to go here.

Thanks for joining me everybody! Today, I will be talking about a new theory of macroevolution that is based on an alternative evolutionary force. So, I would like to start with a little questionnaire, just to gauge what kind of knowledge level we have here. If you would not mind answering these questions, I can get a little feel for the kind of opinions here.

00:02:32

Questionnaire:

Yes/No Questions:

- I generally agree with Darwin’s theory of evolution as an explanation for the diversity of life.

- I have read The Origin of Species.

- I have read any book about evolution.

- Capitalism is successful because it allows Darwinian competition and “survival of the fittest” firms.

Alright, this is great! This is my first time doing a Zoom talk so this is interesting already to see the results coming in. We have about 25 answers. I do not want to bias the results, so I am not going to tell you the results yet. But, I will say that, from what I know about my friends who are evolutionists, most have at least partially read The Origin of Species, and I don’t know how many have studied it super carefully, but most at least peruse it.

Most laypeople I know—maybe about half—have read some book about evolution. Most of them have not read The Origin of Species.

Just to give a little recap:

Questionnaire:

Answers to Yes/No Questions:

- 44 out of 44 generally agree with Darwin’s theory of evolution as an explanation for the diversity of life.

- 8 out of 44 have read The Origin of Species.

- 27 out of 40 have read any book about evolution.

- 18 out of 43 think that capitalism is successful because it allows Darwinian competition and “survival of the fittest” firms.

So, the first thing I would say is that we have so few people who have read The Origin of Species (8 out of 44), but many who basically agree with Darwin’s theory of evolution as an explanation for the diversity of life (44 out of 44).

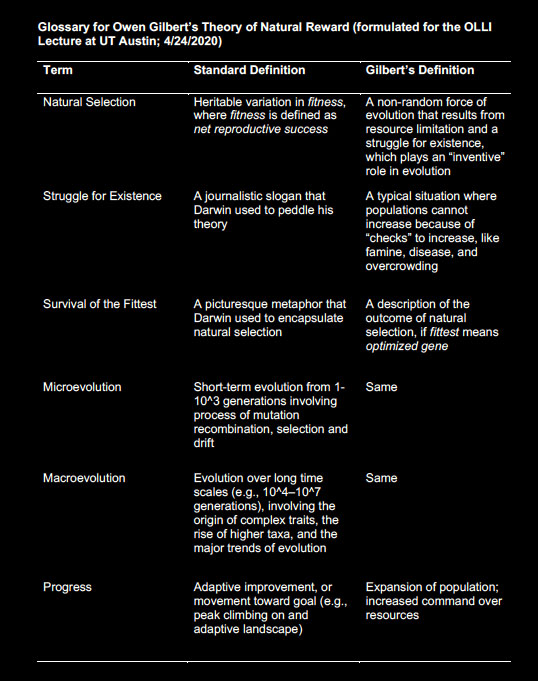

I would suggest that it is important to understand the context of Darwin’s advance to really understand whether it is a complete explanation. And I will get into that in just a second here. I am just going to put up a hand-out with some definitions for anybody who watches this talk later.

(Slides 3 and 4)

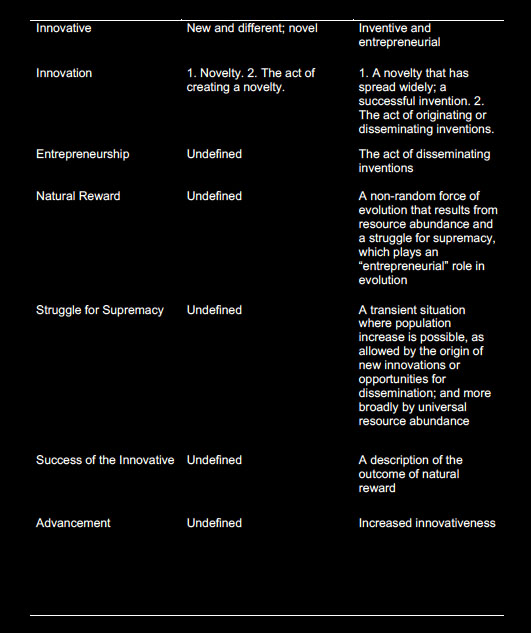

Okay, so we have seen in the poll here people generally think that the main problem has been solved. Out of our audience, we had a hundred percent say that Darwin has an explanation for the diversity of life. That is a result of the modern synthesis, which occurred from 1937 to 1959—when all the experts in biology synthesized available information and concluded that Darwin’s theory is the complete explanation for the history of life (slide 5).

00:07:20

(slide 5)

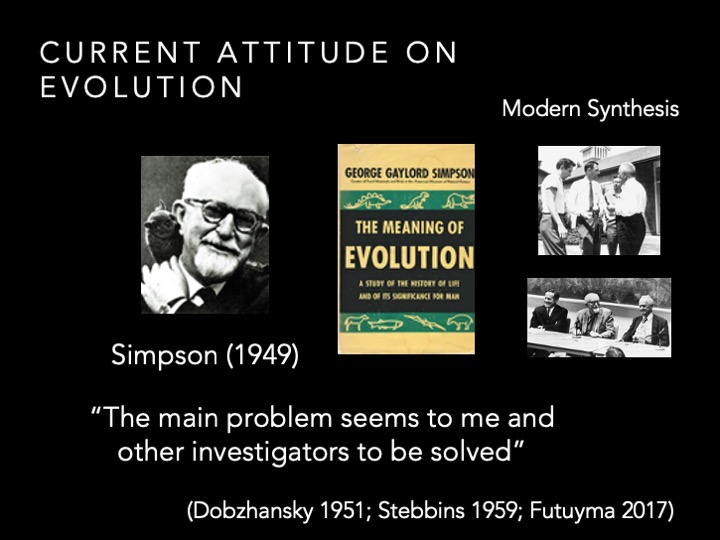

This is the question: where did all of the diversity of life come from? Darwin in his book The Origin of Species was really looking at whether the theory of Independent Creation was correct, so his theory was not directly answering the question of the diversity of life. It was more looking at: were species Independently Created? All of his arguments were against that idea—and instead in favor of species descended from a common ancestor. He had some corollary arguments about the evolution of adaptations in nature that were important for his argument. He ended his book with a passage that suggested that all of this diversity of life had come from evolution (slide 6). So that is why that it looked like his theory explained this.

(slide 6)

So how do evolutionists justify this idea that Darwin’s theory explains the diversity of life? They typically rule out alternative theories of macroevolution, the main ones being saltation, which is evolution by leaps or jerks; or orthogenesis, directional trends of evolution that are unexplained.

Evolutionists typically ruled out these alternative theories by showing, for example, that saltation does not happen, that complex traits go through transitional states; or because there are exceptions to any directional trend in the history of life.

So basically, the neoDarwinians concluded that, because they could rule out these alternative theories of macroevolution, that therefore natural selection—or “modern evolutionary theory”—is the complete explanation. Now, there is a relic of Creationist philosophy in making this argument. It is the same kind of logic that Creationists use when they say, “Oh, well, current science cannot explain the origin of life, therefore it must be God.” So, it is really not a very scientific approach.

The more scientific approach would be to leave some room for the undiscovered, and be agnostic with respect to what the theory can explain.

00:10:30

Darwin’s contemporaries immediately saw that his theory did not explain the major trends of evolution. It explained context-dependent adaptation. It provided a lot of evidence for Descent instead of Independent Creation, but it did not directly predict any sort of long-term trends of evolution. So, Charles Lyell is the first person to recognize this. Right after he read the final proofs of The Origin of Species, he sent over a letter giving some counter arguments. Darwin kept talking about how new forms of life are superior and old ones are inferior, but then the superiority really is only relation to the current climate. So, how does natural selection lead to some kind of overall progress? Lyell challenged Darwin and encouraged him to, “modestly limit the pretensions of selection.” In other words, qualify his arguments—not necessarily bring anything else or supernatural powers (slide 8)—but just say, what exactly natural selection explains.

(slide 8)

Alfred Wallace also saw this problem with Darwin’s theory. Wallace concluded, after looking at humans and all the traits that have fortuitously combined for us to have conquered the world—with our hands, our ability to make speech, our large brains—all these things combined together. Wallace thought because of this fortuitous effect at this larger level, that there must be some other kind of force or law of evolution that we do not understand yet.

(slide 9)

So this is the outline for the talk (slide 10). First, the self-contradiction in Darwin’s theory that his contemporaries immediately recognized. Second, how this affected the development of evolutionary theory since Darwin’s time. Third, I am going to start developing an alternative theory that builds on the strengths of Darwin’s theory. It only accepts one of his messages as correct. I will have two sections that develop this theory. Then I will have a section at the end that gets back to these economic questions. Does capitalism succeed because it allows Darwinian selection and survival of the fittest? Usually when I talk to people and I start putting it into economic context, they say, “Oh okay, I get it now.” So, that will be the last part.

(slide 10)

The reason Darwin’s contemporaries had a problem with his arguments for natural selection as a complete explanation was that he had these conflicting messages. One of them was that natural selection led to superior forms of life: that new forms of life conquer their progenitors, and an overall increase in the advance of organization of life. He basically saw it as a situation where the new forms were better able to evolve and adapt. They were on this overall scale just better than the previous ones. So Darwin kept on using these words like improvement and superior to refer to the new forms of life.

But then in most of his arguments, Darwin said, “Natural selection acts for immediate benefits and it has no foresight for the future…it only adapts to the immediate situation, and that could just as easily lead to extinction as success.” And he emphasized this over and over.

15:00

So Darwin’s contemporary saw this problem. But when it came time to evaluate Darwin’s theory, the authors of the modern synthesis were caught in what Bateson called a double bind. Bateson was a psychologist and he had a theory of schizophrenia. It says that early in childhood development, a child is imposed with these double binds, which are self-contradictory messages that are coming from an authority that the child cannot opt out of. So, when you are growing up you are constantly getting conflicting messages and they are basically very important to you, like, does your mother love you or not? You have no ability to comment on it and you develop in this situation where nothing makes sense to you. So, the authors of the modern synthesis have these two messages coming from Darwin (slide 12), and they were trying to decide which one is correct. They could not comment on the contradiction because doing so would leave the door open for Creationists to teach evolution in high school classrooms. So, what they did was they accepted both messages as correct.

(slide 12)

This leads to a basically a schizophrenic state of evolutionary theory, where we you have these two different views— where natural selection is both a teleological force that works for ultimate benefits —and one that is non-teleological that works only for short-term benefits. So pretty much all major evolutionists have fallen victim to this double bind situation. Just to give an example, Richard Dawkins criticized theories of species-level selection, which assume selection on a long-preserved unit. He advocated an alternative, gene selection. The problem is that genes are also potentially immortal, so it becomes really easy to explain traits by appeal to a long-term benefit to an immortal gene (slide 13).

(slide 13)

Okay, so gene selection does not somehow prevent you from falling victim to a teleological argument, which would be explaining something by its telos or end. You find often in the works of various evolutionists that they are basically advocating both sorts of ideas. You see it in the works of modern synthesis. Dobzhansky understood natural selection theory, and most of his work did it right. But sometimes he would come out with these diagrams that suggest that complex traits have evolved for some ultimate benefit. The most influential was in the third edition of Genetics and the Origin of Species, where he drew an adaptive landscape (slide 14). He changed what the peaks meant. It basically suggested that organisms are optimized to their ecological niches. So, you had different species at the top of the peaks. He talked about different species of cats and dogs. Tiger would be on one peak and lion on another, and puma on another. This would suggest that the they are all adaptively optimized to their ecological niches.

(slide 14)

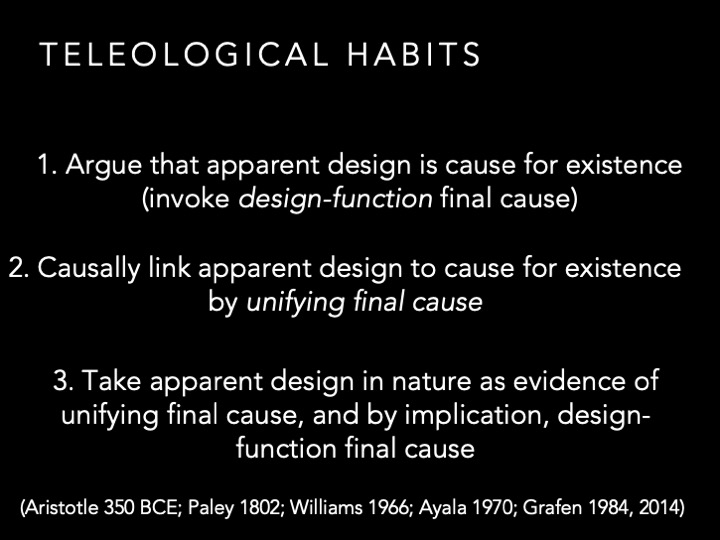

A main problem with evolutionary theory today is that it has reincarnated teleological habits. Teleology is not as simple as getting the units of selection wrong, or assuming that natural selection maximizes fitness of a whole organism or complex trait. It also involves this sequence of habits that goes back to Aristotle and the natural theologians right before Darwin. The sequence of habits is as follows (slide 15). First, when you look at some complex trait of an organism you say, “this complex trait is there for whatever apparent purpose that it serves. So, a wing is for flying, a hand is for grasping, a streamlined body is for swimming, a feather is for flying.” You just look at whatever apparent purpose the trait has you and you say that is why it exists. That is the first part. I call that appealing to the design-function final cause.

00:20:24

The second part is deriving a unifying final cause that explains the causal link between the apparent design and the cause for existence. For Aristotle, the unifying final cause was, “nature does nothing in vain.” For the natural theologians before Darwin it was, “so it pleased The Creator.” So for example, a fish has a streamlined body because it pleases The Creator or “nature does nothing in vain.” For the neoDarwinist now, the unifying final cause is usually fitness maximization. This links all of the design functions to their cause for existence.

(slide 15)

So then the final part of the sequence of habits is that you look into nature and you see all this design, you take it first as evidence of the unifying final cause. For the natural theologians, you look into nature, you see all this wonderful design, and you see Creation. For the neoDarwinist, it is fitness maximization. For some, it is gene selection or something like that. So, then you take design as evidence for this unifying final cause, and then by implication, that justifies your taking the apparent design as evidence for the cause of existence.

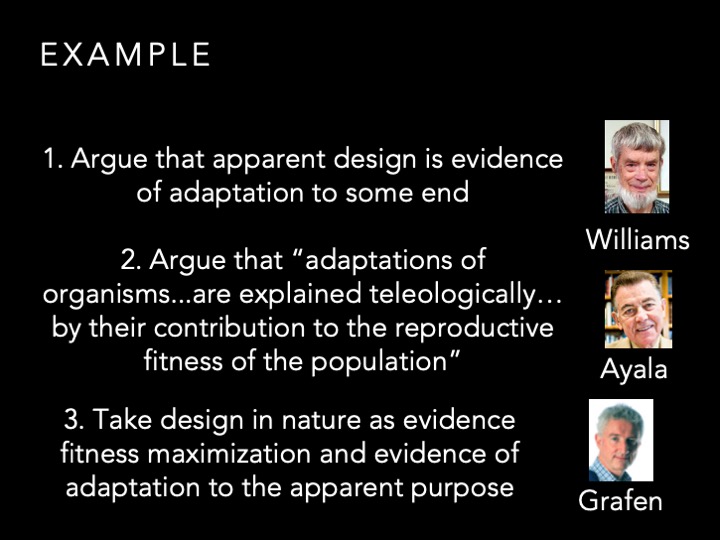

Different individuals have gradually built up this paradigm starting with G. C. Williams (slide 16). This is ironic because Williams was trying to argue against teleology and he just created a different brand of it. Ayala argued for teleological explanations in biology. More recently, in the especially in the fields of social evolution and quantitative genetics, this has really become a big deal. The last part of it is the empirical component—basically studying a bunch of traits in nature and taking them as evidence of theory without ever testing a hypothesis.

(slide 16)

So one of my main challenges is getting out of this teleological way of thinking and getting out of the Darwinian double bind that has created this kind of schizophrenic atmosphere in the theory. People basically have no sense of reality, and they are taking data to be supportive of a theory that does not make sense. It is pseudoscientific because of this large empirical component. For example, astrology and psychoanalysis had an empirical component that does not really test anything. It cannot falsify itself. You are going to nature and you are saying all of this is evidence for fitness maximization and by implication, whatever function the trait appears to serve. Then you can go about your research and never actually have any possibility of disproving your hypothesis for why something exists.

I have come into contact with this paradigm in my own field and it raises the question, especially when people are totally resistant to new ideas: how do you get out of it? Darwin ran into the same problem (slide 17). His solution was, “Do not even try to communicate to the people who are so far biased that they spent their whole career and life looking at the world from a teleological standpoint.” Darwin therefore appealed to a new generation of workers and in fact, that is how his theory became adopted. I too am going to try to appeal to impartial third parties outside of my field. That is partly why I am writing a book on this topic. I am trying to communicate to people who are either up-and-coming, or who are outside the field. That is also why I am talking here. Most of you are not biased by a lifetime of doing a research a certain way. So, you can look at this from a from an outsider’s perspective.

(slide 17)

00:25:00

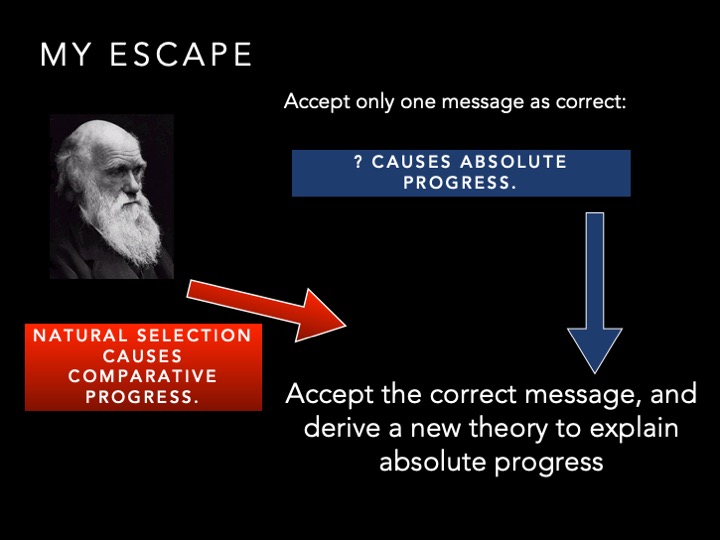

What I am going to do here to escape this double bind situation, is just accept one of the messages as correct. The correct message coming from Darwin really is that natural selection creates comparative progress—meaning, you just adapt your context-dependent situation. Natural selection does not have any foresight for the future.

(slide 19)

So that then raises the question of what causes this absolute progress that we see going from simple to complex and the major trends of evolution. So, that is where I am going to start here in just developing this new theory. The first part of this theory is the struggle for supremacy.

Comments on Part 1 in Reflection

I was surprised that 100% of the audience said that they thought Darwin’s theory of evolution is an explanation for the diversity of life. Upon inquiry, some audience members later told me that this was a political stance. They wanted to show support for science. I think they were pleasantly surprised that supporting science does not require adherence to a particular scientific doctrine! Most of all, they were happy to find out that new discovery is still possible.

In my paper, Natural reward drives the advancement of life, I give an example of the three teleological habits in action. This example is from the study of kin recognition, which is one of my areas of expertise. I may discuss this example in a future blog post.